The Bluestocking: It's A Sin Special

When I look back upon my life / it’s always with a sense of shame

Happy Friday!

(spoilers for It’s A Sin abound beyond this point)

This week I finished watching It’s A Sin, Russell T Davies’s five-part drama about the Aids epidemic, which follows the lives (and sometimes deaths) of five London flatmates: flamboyant Roscoe Babatunde, disowned by his religious African family; Ritchie Tozer, an aspiring actor from the buttoned-up Isle of Wight; Ash Mukherjee, a very tall guy Ritchie meets at university; nerdy Welsh trainee tailor Colin Morris-Jones; and endlessly supportive Jill Baxter.

Now, I have no hesitation in recommending It’s A Sin. It’s peak RTD: the early episodes have all his bouncy labrador energy, as the guys move to London, overcome their repressed upbringings and shag around like there’s no tomorrow. Which is, of course, the problem. Alongside all the spangles and karaoke and thrusting, the show never lets you forget that for some of its characters, thanks to the shagging, there will be no tomorrow.

Neil Patrick Harris’s arch, dapper Henry—who saves Colin from their slobbering boss—is gone before the end of the first episode, dying alone in a locked, empty hospital ward. It’s an image of intense inhumanity, driven by fear of this terrifying new virus. The first two episodes have several other images which are just powerful. The baby pictures of Gregory, the gang’s Scottish friend, smoulder on a pyre as his family burn all his “dirty” belongings after his death. All his potential life, gone up in smoke. Ritchie’s agent asks him the standard job interview question: Where do you see yourself in five years’ time? To which the audience, as Ritchie flusters and gushes, mentally supplies the true answer . . . dead. (I’ve been nursing a theory that great television drama asks its viewer to supply the missing half of the action on-screen: don’t go in the basement! she’s not your real wife! oh my god, she’s going to kill him! That turns watching TV from a passive to an active process, making it much more engaging.)

The hypocrisy which stank out the 1980s is lightly, rightly skewered. That slobbering boss first sacks Colin for being gay and then turns out to be getting noshed off in toilets himself. Stephen Fry’s panto villain Conservative MP wants Roscoe to play nanny to his bad, bad boy, before angrily declaring that of course, that doesn’t make him gay.

For me, episode 3 is the highlight—a strange word to describe something which reduced me to helpless sobs. RTD has always prided himself on writing like Dickens—with more dicks—and his best work is unafraid of big emotions, bordering on melodrama. It’s why he was such a great writer of Doctor Who: his set-pieces demand death, birth and/or saving the world, to give his characters a grand enough arena. It might also be why he’s so interested in sex, as another kind of transcendent, pure human experience. And also, because, as Ritchie says on his deathbed: it’s fun. Davies is a writer who revels in fun, particularly young fun, all those house parties and uni halls and karaoke and crappy jobs that you don’t mind because you have your own money and you’re living your own life.

RTD is the opposite of a puritan, which is central to the arc of Ritchie, the lead character of It’s A Sin. The show tells a realistic, difficult story about Ritchie’s terror of AIDS, which paralyses him to the extent he refuses to get an HIV test. He lives in denial—worse than that, he knows, deep down, having seen his boyfriend’s sarcoma, that he is probably infected. But he resists that knowledge until the last, and carries on sleeping around.

I find it hard to judge Ritchie for this, and so does the show—in frightening situations, we don’t all grow into heroes, some of us shrink into cowards. Yet instead of making us sit with that discomfort, it decides to dump all the blame onto Ritchie’s mother. In a final confrontation, Jill tells Valerie Tozer (Keeley Hawes) that she is not just responsible for Ritchie’s lonely death, but for all the lonely deaths of the boys who died from AIDS. Killed by sex they were told was dirty, and they had to hide. The Pet Shop Boys lyrics which provide the title sum it up: “When I look back upon my life /

it’s always with a sense of shame / I’ve always been the one to blame / For everything I long to do.”

Before going on, I have to state that this is a great scene in dramatic terms. Jill comes to the meeting, expecting to be told she could see Ritchie at last, only to be told he has already died— and the ambient sound of waves and seagulls suddenly drains away, yielding to a rushing silence. It’s a beautiful televisual rendering of the whomp of bad news, the sensation of the world narrowing to a tunnel, the nauseating knowledge that everything has irrevocably changed. This scene also serves an obvious dramaturgical purpose, to summarise the polemic message of the show: society saw gay sex as a sin, and Aids as divine retribution, but the real sins were the inhumanity, hypocrisy and cruelty of society.

To me, loading all that on to the single character of Valerie seems unfair. Why her alone? Her husband, also a homophobe, rages for a bit after hearing about Ritchie’s illness then settles down to crying and reading him stories. Roscoe’s dad, also a homophobe, gets a redemption arc after visiting an African AIDS hospital and witnessing the inhuman conditions there. Jill and Colin’s mums (the former played by the real-life Jill, Davies’s friend) are blamelessly supportive. Jill’s mum even comes on a demonstration; so does Colin’s, in her wheelchair.

Ritchie himself is forgiven many sins: ghosting his boyfriend when he sees his sarcoma; only coming on the anti-Aids demo after a last-minute change of heart, having previously put his acting career first; shouting at a housemates’ dinner that he’s bored of them endlessly talking about Aids; borderline sexually harassing his old schoolfriend on the beach. We understand that he’s frightened of death and trying to push away the knowledge of its inevitability.

My hunch is that Davies wanted to gender-swap the expected denouement, and demonstrate that homophobia does not only manifest as gay-bashing—which is overwhelmingly perpetrated by men—but subtler, insidious cruelty. But turning Valerie into the show’s avatar of homophobia made me think: would most people react well to the news that their son has concealed his imminent death? Mightn’t we all freak out and say awful, regrettable things?

Also isn’t Valerie’s sin the same as Ritchie’s—denial? She has no time to work through the social conditioning she has received (there are passing allusions to her father being a monster) before Ritchie’s death. Just like Ritchie, she pushes away the dreadful certainty of knowledge. He can’t have cancer, he’s too young! These doctors don’t know what they’re talking about! Only I can take care of him! Her arc follows the same path as Ritchie’s, desperately refusing to look the disease in the face.

This is a scene about which sins deserve punishment, and Valerie is, undoubtedly, cruel to Ritchie’s friends, to a monstrous degree. One of the most affecting notes of the series is how much lonelier these young men’s deaths were than they had to be. Although talking of callousness, a strange piece of plotting happens in the final episode, presumably to set up the final confrontation as a two-hander. Ash—by now Ritchie’s boyfriend—decides not to come to the Isle of Wight to see him for the last time, even though Ritchie’s agent gives the housemates the money to do so, because he “has to work”. Really? You wouldn’t go see your dying boyfriend on, like, a weekend? Ash is excused this, just as Ritchie is absolved of killing the men he slept with. (The script also glosses over the fact that Colin’s mum Eileen being supportive didn’t mean his life was spared. Being brave gets no one off the grave, and neither does having a loving family.)

People might groan at this—come on Helen, it’s a show about a disease which overwhelmingly killed men, why are you harping on about women?—and that’s a fair point. I have no issue with this being a story which puts gay men front and centre. That’s where they deserve to be. And perhaps I’m coming off as Valerie Apologist, when the show very clearly makes the case that what she symbolises—the casual, cruel, nervous homophobia of the 1980s—is absolutely repellent, a stain on society. And maybe it is more monstrous coming from your own mother, the one person whose love is supposed to be unconditional.

It’s A Sin convincingly demonstrates that the Aids crisis posed a great challenge to society, one which (largely) it failed to meet. Could straight people sympathise with victims of a disease spread by pleasure? No. The moralising overtones of the panic are captured nicely in Chris Morris’s “Bad Aids” sketch.

But all the way through the last two episodes, I kept thinking about Queer As Folk.

Queer As Folk was maybe the defining show of my adolescence. I loved it.

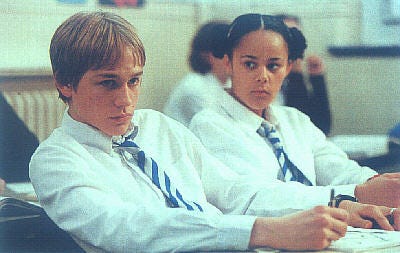

It followed three gay men, who you can see as three aspects of Davies’ own personality. Nathan was the brave teenager embracing his identity; Stuart was a rich, swaggering shagger, a pure id on legs; and Vince was the sweet Doctor Who fan, secretly in love with Stuart.

Putting Queer as Folk and It’s A Sin next to each other is illuminating. First, consider their differences—behold the 1990s, where you could do a show about “gay life” and have all the publicity materials feature three white men. The default whiteness of 1990s television is even more striking when you look at the cast for the US version.

It’s also notable that Queer As Folk didn’t follow Davies’s current stricture that gay roles should only be played by gay actors. (All the lead cast in It’s A Sin are gay and out.) In QAF, all the leading men were straight in real life, and you can see how that might have cheesed off their gay contemporaries who’d been told to stay in the closet, as the trio were commended for their “bravery”. But the pool of out gay actors was much smaller in the 1990s: Rupert Everett has written powerfully about how coming out ruined his career. You can make a good case that it was better to get QAF made with straight men than not made at all.

The similarities between the two shows are just as interesting. I suspect my reveries were sparked by the bingy-bongy soundscape—a glockenspiel?—of It’s A Sin, the work of Murray Gold, also RTD’s composer on QAF and Doctor Who. Those bing-bongs are so reminiscent of Queer As Folk’s theme music. (Incidentally, no show has made a better case for the emotional range of 80s pop music than It’s A Sin, while QAF does the same for the 90s.) As well as the same composer, the new series reunited Davies with his longtime producers Phil Collinson and Nicola Shindler.

It also had, let’s not be coy, some of the same characters. Roscoe is heavily influenced by don’t-give-a-fuck Stuart: the scene where he waltzes out of the Commons, having pissed in Margaret Thatcher’s coffee, reminded me of Stuart turning up at the school gates to collect Nathan in a jeep spray-painted with gay slurs. You call Stuart a cocksucking queer, and his response is: yes, isn’t it great? I love cock! Both characters are a shrug in human form. So life deals you a terrible hand: sod it! have fun!

Adorable Welsh Colin, meanwhile, is Vince redux: he loves men rather than just wanting to fuck them. (He lusts after Ritchie just like Vince lusts after Stuart.) Vince’s supportive mum Hazel becomes Colin’s supportive mum Eileen. There are lesbians on the periphery of QAF—Stuart donates his sperm to two female friends to have a baby—but it’s firmly a gay show rather than an LGBT show. So is It’s A Sin.

Then there’s Jill, Ritchie’s endlessly supportive friend. In the 1990s, Jill was Donna:

She was the best friend every gay boy needed in the 1990s. She loved hearing about his shagging and the adventures, and staunchly defended Nathan against the bullies.

Queer As Folk came out in 1999, and here I am, gushing about it two decades later to Russell T Davies himself, when I profiled him for the New Statesman:

Within the first ten minutes there’s an orgasm and the arrival of a new baby. (The orgasm – Nathan’s – happens while Stuart is hearing about the arrival of the baby, the phone held in his other hand.) Drugs are taken, Stuart’s car is spray-painted with homophobic graffiti and Vince pulls a man who turns out to be wearing a plastic six-pack mould under his T-shirt, covering a generous belly. This was gay life without shame and without apology.

[…]

I was captivated by Queer as Folk when it first aired, because I was the same age as Nathan – 15 – and his story is that of a teenager trying to establish his own identity. “Which isn’t gay at all,” Davies chips in. “It’s why you were sitting there enjoying it. Not many programmes still today [show] the young clubbing, and not telling them off when they take drugs or get drunk. Television’s still quite judgemental.”

Queer As Folk didn’t mention Aids—something Davies was questioned about at the time—and there’s a good reason for that. It’s a fairytale, loaded with wish-fulfilment. It’s A Sin is its shadow, the dark reality. It strives to be just as non-judgmental about drugs and casual sex as QAF was, despite juxtaposing Ritchie’s lifestyle against its consequences. Davies wants to smash the idea that gay sex deserves punishment. In QAF he did that by showing a fantasy, while in It’s A Sin he confronted reality.

Three years on, though, what I said about Nathan now strikes me with greater force. Because I did want to be Nathan. But the world wanted me to be Donna. The world wants me to be Jill.

As a teenager, two male friends chose me as the first person they entrusted with the secret of their sexuality. Coming out was a scary thing to do in the 1990s, particularly as they were both at all-boys’ schools. My first boyfriend was also gay, something I knew before we started dating (a story for another time). I spent quite a bit of my teens wingmanning him in pubs and clubs, ready to be deserted without notice if he found someone to get off with. Those boys needed my support, and I was glad to give it. One of them was very into cottaging—giving blowjobs to random strangers in public toilets—and while I couldn’t see the appeal myself, I knew that he didn’t have the same dating options I did. When my gay boyfriend and I broke up—spoiler: it didn’t work out because he was gay, which I should have seen coming, for all I cried to “Careless Whisper” in the taxi home—he said it had been a nice relationship, because he could hold my hand in public.

Talking to other female friends, they have similar stories. We picked up the boys who were scared, and isolated, and we tried to make everything OK. We were proud to be their friends, to help them find the scene, even though gay clubs could be hostile to women—why are you here, no one wants to fuck you—because who doesn’t stick by their friends?

But It’s A Sin prodded a feeling that I had buried. Before their final confrontation, there’s a scene in the last episode at the hospital between Valerie, Ritchie’s mum, and Jill. It ends with another mother of a man on the ward haranguing Valerie for not knowing until now that her son was gay: when you looked at him, why didn’t you see that? Why didn’t you know everything about this boy you claimed to love? It’s presented as a punch-the-air moment, but I found it uncomfortable, even cruel: Ritchie hid his sexuality from his parents—presumably quite well, he was an actor! And all this is happening mere moments after Valerie learned that he was dying. It added to my feeling of her as punching-bag for the wider sins of contemporary society.

We might not question this too closely, because minutes before, Valerie has been set up as a villain. Trying to make sense of Richie’s terrible news, she starts talking to Jill about how men go “rutting” in their 20s because they’re so randy and, duh, it doesn’t mean they’re gay. (Which is a sentiment I remember hearing in my own adolescence.) And yes, OK, so they all have boyfriends, she tells Jill: where’s yours? what’s in this for you? Maybe Jill’s angelic selflessness is too much for Valerie to bear, perhaps because she already senses that her own instant reaction has been so mean and small.

Still, those lines about Jill’s non-existent boyfriend reminded me of a phrase Davies uses in The Writer’s Tale, a book of the letters he exchanged with the editor of Doctor Who magazine during his time as showrunner. He calls it “hanging a lantern”—fronting up a plot hole by mentioning it, so it can be dismissed by a character on-screen. It obviously works well on a mid-budget scifi show—“why can’t we just blow up the base?”/ “no, it would never work, because of the anodyised interceptors and the sequencing sprocket”— but it works just as well here. Why doesn’t Jill have a life of her own? Ssh, you don’t need to know. Move along. Hanging a lantern tacitly admits that Jill is more of an emotional support peacock than a fully rounded character. Her characterisation means that both sides of the current split in the LGBT movement can identify with the show. I’ve seen several gay men read the show as an indictment of the opponents of self-ID, with Valerie as the purse-lipped reactionary holding back the new frontier of equality and progress. I’ve also seen lesbians read the show as further evidence of the lopsided nature of the LGBT movement, where women are expected to give support and solidarity but are scorned for asking for it themselves.

It is both and neither; like I said, a drama exists as a relationship between author and viewer. Your It’s A Sin is not my It’s A Sin. Those who lived through the events depicted will have watched a completely different programme to the one I saw. Those who identify strongly with Richie will take away different memories from the Colins, or the Roscoes, or the women who feel that if they offer anything less than full support for the men in their lives, they are moved invisibly from the category of Jills into the bucket of Valeries.

One of the hazards of The Current Discourse is that some people will read this as me “attacking” the show, or excusing homophobia. That’s not my intention at all. I’m pointing out what a brilliant dramatist Russell T Davies can be, and the discomfiting questions below the surface of It’s A Sin. RTD can make you think as well as feel. He can do highs and lows. He can create believable families—both of blood and by choice—and flawed protagonists you nonetheless hug tightly to your heart. He can make you ask yourself: whose sins can be forgiven?

If the new show feels like an echo of Queer As Folk, that is possibly because it was always lurking underneath the surface of its predecessor, unspoken, drifting behind the lines. Maybe the 90s of Queer As Folk are so fun because the 80s of It’s A Sin were so traumatic.

Did I mention that you should watch it? You should definitely watch it.

Until next time,

Helen

PS. I sent this essay around a few friends before publishing, and one of them—a gay man, as it happens—pointed out that Jills aren’t that rare, and often attach themselves to gay men. These women are what we used to call “fag hags” (not sure there’s a 21st century approved version of that). This is a fair point. There is a strong streak in some women, whether from hormones or socialisation, which is bound up with taking pride in being caring or even overtly self-sacrificing.

A fantastic essay, Helen, that explains much more articulately - and generously - than I could why I have been banging on about Jill and Valerie over the past few weeks. Jill, in particular, seemed such a thin, barely-sketched character whose job was simply to be endlessly affirmative., The final scene in which she tip toes into a stranger's hospital room as he lies dying of Aids and holds his hand seemed really quite odd - possibly I am not a very altruistic person but it struck me as intrusive and quite needy on her part.

I was a child and teenager during the 80s and Valerie's attitude wasn't uncommon, it was mainstream so putting her on a pyre was unfair. As you wrote, it was more about creating a big final flourish than revealing a truth - I don't think we can blame Valerie for not being a social outlier, especially when her son chose to hide his sexuality despite infinite opportunities to explain why he and Jill weren't a couple, why he wasn't going to settle down with a nice girl soon etc. (I have teenagers in my life, however, and they are equally sure that Valerie really does bear the responsibility for all Aids deaths but, hell, when was a middle-aged woman not to blame for everything that's gone wrong?)

Thank you for your generosity in sending out the newsletter each week - I'm going to start rewatching QAF with one of the teenagers tonight.

I loved both of these programs too, I can't watch It's a Sin again as after the 1st and 2nd times I discovered that AIDS cannot possibly be a sexually transmitted disease as it is only correlated with frequency of receptive anal sex, in both genders. AIDs is an illness of oxidation and semen is highly oxidising and the anus cell layer is very thin. Then I found out that Kaposi Sarcoma and PCP are known to be caused by popper inhalation and that the initial treatment of AZT ,a failed cancer therapy drug, is highly oxidising and toxic and undoubtedly killed many people after they received a positive test.(and were locked away in wards on their own)- I am too upset and angry about this to be able to watch it anymore.

The (non-specific )HIV test is based on the proteins and antibodies (PCR cannot be used as there are billions of different sequences thought to be the HIV genome) which are also found in healthy people, TB and pregnancy etc. The test has to be confirmed by a doctor, based on patient history- blood transfusions ( though a virus would not survive the process intact), and whether the person is a Black African or a gay man. This is so far beyond the scientific method as to be mind blowing. Many people took their own lives on a positive result for a thing there's no evidence causes illness.

Anyway the two videos linked in my post are well worth watching https://georgiedonny.substack.com/p/the-importance-of-intellectual-freedom?s=w if you haven't seen them.

Really enjoying your posts I just discovered this morning

Jo