Surprise!

I know I said there was no newsletter this week, but I’ve been brewing this post for a while and since I just signed off a longread for the Atlantic, now feels like a good time to reflect on the process of reporting and writing at length.

Feel free to skip this one if it feels like journalism inside-baseball, but I think some of it might apply to other disciplines, too.

Helen

Helen’s Big Rules of Writing

Notice what you notice. John Lloyd, the great comedy producer, once said to me that the best comedians use the audience as an editor: the audience are the experts: they know what’s funny. Something similar is true of journalism: you are a human being encountering the world, and if you find something interesting, the chances are, so will other people. If you find your brow furrowing, don’t be afraid to ask the question that just popped into your head.

The main reason people don’t do this is that they want to seem cool, or knowledgeable, in front of their interviewees. They don’t want to risk asking a stupid questions. Always ask the stupid question. Not least because if you don’t, you might come back, write up your piece and face an editor going, “so what did she mean by saying she lost her virginity to a goat?”

Details are everything. Imagine someone who drives a beaten-up Vauxhall with the footwells full of crisp packets. Now imagine someone who drives a prototype Tesla truck. Now imagine someone who drives a vintage Lotus Elise, its fittings polished to perfect brilliance.

One of the most beautiful things about reporting—going out in the world—is that humans are surrounded by a penumbra of information. Their hair, their clothes, their voice, their volume, their vocabulary, their cultural references. On the page, those details do so much heavy lifting for you. It’s why screenplays can be so much more sparse than novels. Once you see the actor, that’s worth five paragraphs of prose describing a character. (A friend is insistent that the actor playing Andrey in Three Sisters cannot be hot, because you need to understand instantly that everyone’s faith in this golden child is horribly misplaced.)

Many writers now feel uncomfortable about physical descriptions, in case they sound judgemental. That is a risk—you should not be cruel—but if someone has blue hair or wears spats, they are trying to tell you something about themselves and it’s OK to notice that.

Added to that, details make a piece feel concrete, connected to the world, real. I loved Stephen Greenblatt randomly melding his Silly Putty in Nathan Heller’s recent New Yorker piece on the humanities. Why does he have silly putty in his office? Is he 7? Is he very stressed? It’s a little detail that reminds you there’s a real person and a real conversation happening in the piece.

All the pieces I did over Zoom I found a little frustrating, for this reason—as does so much writing about internet communities and their drama. It all happens in this weightless realm of nothing.

This is from the first section of my feature in Albania to show you what I mean:

And here is the prince: 39 years old, more than six feet tall, with a sandy beard, navy blazer, and soft South African accent, saying goodbye to his wife, Crown Princess Elia, and their 1-year-old daughter, Princess Geraldine. The pair are about to go to the park—without bodyguards—and Prince Leka II takes me inside, to the drawing room, where the faithful retainer brings me an espresso. Next door is a room devoted to Albanian history (“what a lovely scimitar,” I find myself exclaiming, my reserves of small talk inadequate at the sight of the family’s sword collection), and beyond that is a cozy lounge with a leather sofa, its domesticity slightly compromised by the bows and arrows hanging on the wall.

Don’t be braver on the page. What I mean by this is—if you plan to make a spicy observation about someone in your copy, make it to their face. Give them a chance to respond, first of all, and not to feel misled by your approach. (Don’t be nice as pie to an interviewee and go to your laptop and zing them, it’s not fair.) Also, confrontations done right are clarifying: your interviewee might offer a perspective you hadn’t considered, or an insight into their own life. They might even change your mind.

Don’t save people from themselves (too much). As a writer, you have an ethical responsibility to people you write about: don’t lie about them, don’t set them up, don’t mischaracterise them. But also: don’t impose your values onto them. If you are talking to an adult and they tell you something that makes you uncomfortable—about their private medical history, past addiction, odd sexual fetish—resist the urge to tidy that away.

Instead, repeat it back to them and see if they panic horribly because they said it to a journalist, or in fact if they wanted you to know, because they are trying to smash the stigma around depression, or they are an adult diaper activist, or whatever it might be. Just because you wouldn’t want to talk to a stranger about your rape, don’t make that decision for someone else.

I am constantly surprised by what people tell me on casual acquaintance—I always assume that everyone is wary about the media—but for many people, speaking their experience out loud is almost a compulsion. It takes something that happened to them privately and makes it real, makes them feel seen. (The awkward corollary to this is that you then have to tell people you will need to fact-check their intimate story before publishing it. But again, most people are more chill than you’d think about this. They appreciate the idea that journalists don’t just repeat whatever they’re told.)

Observe the interview rule of three. Can’t remember where I got this tip—maybe a Cory Doctorow interview? But it was to come away from an interview and immediately write down the three most interesting takeaways from it. Particularly for projects where you are interviewing many people over many months, it will really help to flick through these little summaries of your interviews before sitting down to write. (One of the worst moments in any longread is realising you have 40 hours of tape to revisit.) But where should you write such things down? Aha—

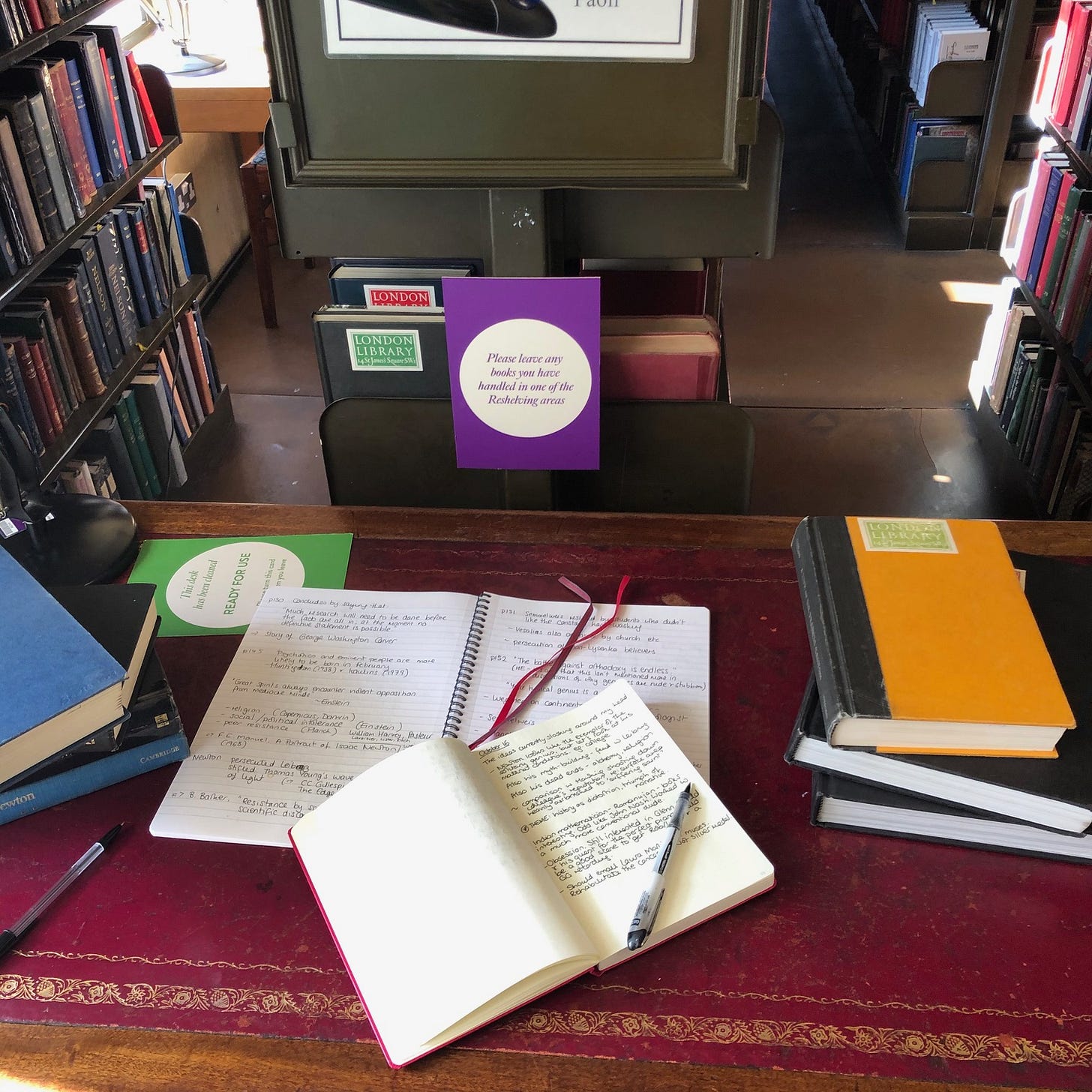

One Notebook To Rule Them All. A few years ago, I started buying Leuchtturm dotted notebooks in jaunty colours. I now use one per project, and I can’t tell you how helpful it is to instantly identify the repository of all my notes on a topic. I also use them as bullet journals, stopping every month or so to write myself a diary entry on how the project is going, what concerns I have, what I’m missing etc.

Log your process. My last few Atlantic longreads have taken around six months from the start of reporting until their eventual publication. (Along the way, I will write shorter, news-reactive articles too.) That carries the very real danger that you will have started to forget things you have stored only in your brain.

These days, for any longread or other long project, I am fastidious about noting down who I’ve requested to interview, when, and if they replied or declined. I can’t tell what a relief this is when your factchecker or editor asks if you requested comment and you can instantly answer without searching your inbox.

I also create a bookmarks folder of all the pieces I’ve read for research, and paste relevant chunks from them, plus the attribution, into a Google Doc. I note the dates of any events I attended, and often also create a timeline of key events I’ll be referencing in the piece. I take screengrabs of any tweets or other social media posts I plan to quote, in case they get deleted.

Email like everyone’s watching. Particularly when dealing with political or sensitive requests, don’t write anything in your emails to sources and official bodies that you wouldn’t be happy to have published.

Know your limits. It’s very, very hard to write for more than four concentrated hours a day. Plan accordingly. The rest of your working time can be reserved for answering emails, conducting interviews, reading research materials. But don’t think you can do a huge burst of getting stuff on to the page at the end of a project.

If you must chain-smoke your writing in the last hours before the deadline, break up the time into sections (use the Pomodoro technique) and build in plenty of snack breaks, walks and interludes doing engrossing but low-brain-use activities like playing a videogame or doing the washing-up.

Know the difference between plot and story. This one is why it’s useful to study screenwriting if you want to become a better longform writer. Any narrative told at length will involve a series of incidents. In the wrong hands these could seem random, unconnected, confusing. What unites them is a story—in my two most recent Atlantic print features, how Europe turned against monarchy but is now turning back; how institutions dealt with the revolutionary spirit of 2020 by sacrificing a scapegoat.

If you ever wonder if a scene or quote belongs in a piece, ask: does it serve the story? Or is it just … an interesting thing that happened?

Sing the theme tune. But there’s more! Often, really great films/novels/longreads will have a theme as well. My go-to example of this is Amadeus, where the plot/story concerns the rise of idiot savant Mozart and the fall of the earnest plodder Salieri. But the theme is envy. There are a million ways to tell the story of Mozart, but Peter Schaffer deliberately decided to tell it through someone else, to make it a reflection on how it feels to be ordinary in the presence of greatness. (Hamilton has the same theme: Burr is eaten up by jealousy for Hamilton, to whom everything seems to come so easily, and that forms the backbone of the story—the scene in the bar, Washington’s choice of staff, the federalist papers, the duel.) In my Albania piece, the theme is monarchy—why do humans have this desire to bend at the knee? In my gurus series, the theme was worship. Maybe not all brilliant longform journalism can be summed up in one word, but a lot can: Jennifer Senior’s Pulitzer-winning 9/11 feature is about grief. “Frank Sinatra has a cold” by Gay Talese is about celebrity.

Park downhill. At the end of every day, finish your writing by stopping halfway through a thought—maybe even halfway through a sentence. That way, there is a small task to complete the next day, helping you navigate the hardest movement in a writer’s life: sitting down at your desk.

Questions? Arguments? Anything I missed? Leave a comment.

So interesting thank you Helen :)

I’m a management consultant and, oddly, there’s a lot here that resonates. I do *a lot* of discovery interviews (what’s going on/ what’s going wrong/ who’s the issue) and it’s about looking for the theme and the story. I love the detective (nosy!) element of my work and weaving together a compelling diagnosis

I am also constantly astonished at what people tell me! It’s like the act of being really listened to, by anyone, for any reason, people will use it to say what they need to say, regardless of the question asked

Nice piece! Thought a lot of this was really useful for previous me, when I was doing a PhD... unfortunately abandoned in a tsunami of chronic illness and anxiety about bloody writing. Mind and body in conspiracy for badness... It took me a long time to allow myself to fold. But (finally) a good decision nonetheless. So your thoughts are really pertinent for me if I let myself sink into Coulda, Woulda, Shoulda... but thankfully I don't.