Happy Friday!

Back at the beginning of the summer, when it was objectively too hot, we recorded Series 2 of my Radio 4 comedy(ish) series, Great Wives.

The first series came from an idea I had listening to Matthew Parris’s brilliant series Great Lives, where a celebrity nominates a person from history and explains why they find them fascinating. (The wonderful Sophie Scott just picked Hattie Jacques, in case you’re wondering, but I also particularly recommend Janine Di Giovanni on Josephine Bonaparte; Chris Tarrant on Kenny Everett; and AA Gill, trollish as ever, on Neville Chamberlain.) I love Great Lives, but how about … Great Wives?

For the last few years, I’ve been thinking about the stories we tell about high achievement, and it strikes me that the Great Man Theory of history is alive and well, despite repeated attempts to debunk it. So I wanted to tell the stories of some of the people around the “Great Lives,” who might have contributed to their success.

Hence Great Wives.

The voices of everyone from Catherine de Medici to Eleanor Roosevelt to performance artist Ulay are provided by Joshua Higgott and Kudzanayi Chiwawa, and the series was produced by Gwyn Rhys Davies. Here we all are, appreciating that the recording was over and we could switch the aircon back on again.

There are four 15-minute episodes, and I will warn you that they are EXTREMELY RANDOM, in that I may be the only person in the world equally interested in the Krankies, Wu Zetian and the widow of McDonalds’ founder(ish) Ray Kroc.

The first episode is on today at 14.45 on Radio 4, and BBC Sounds straight after.

Helen

The Yoghurt Kingpin, The DJ, And The Coup (Garden of Forking Paths, Substack)

Here’s a strange fact about me: I once had to get a rabies vaccine after I was bitten by a lemur in Madagascar the day after I had breakfast with the former president—a yogurt kingpin who got overthrown by a 34 year-old radio DJ in a 2009 coup d’etat.

Fourteen years after that coup, the radio DJ—a secret French citizen ineligible to serve in public office—is again the president and the yogurt kingpin is trying to unseat him in elections later this year. Another coup is not out of the question.

Madagascar is the most interesting place you probably know nothing about. When I first rang up my bank to let them know that I’d be traveling to the island for my research, the woman I spoke to asked me if I was sure that it was a real country.

“Madagascar?” she said, puzzled. “I thought that was a children’s cartoon. Are you sure that’s a country?”

I wouldn’t have discovered Brian Klaas without Substack. I enjoy his (often quite random) newsletters enormously. This one is about Madagascar’s elections later this year, in which the current president is technically ineligible to stand because he is no longer a citizen of Madagascar, having taken French citizenship as an insurance policy against being forced into exile.

Bluestocking recommends: I am upgrading my praise for A Strange Loop, the Pulitzer-winning musical which is in its last weeks at the Barbican.

Although I think it kinda collapses in the second half, and I find the “inner white girl” business quite hashtag problematic, I have been listening to the Original Cast Recording non-stop in the gym and it’s strangely motivating and beautifully written.

Warning: the performance is very explicit in terms of sexual depictions and racial/gay slurs, so it’s not for everyone. And you absolutely cannot sing along to any of it in the car or you will be cancelled.

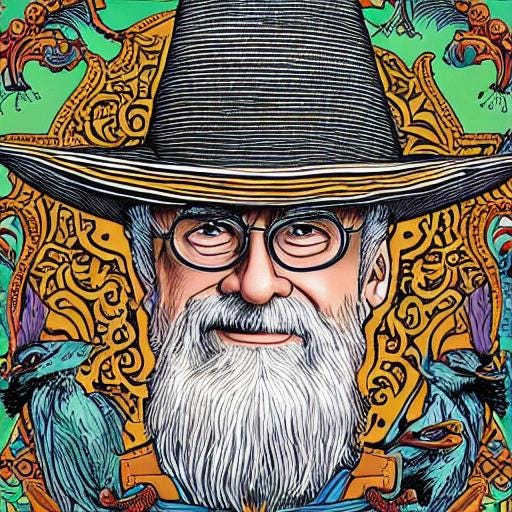

Intermission: The Guardian’s Sam Jordison asked me for a quote on Terry Pratchett’s relevance today. And I ended up writing a bit of a blurt, which is reproduced below. I suspect the peg for Sam’s piece is that there is a new Pratchett biography coming out this autumn, and I have to say, I have zero interest in reading it. On the evidence of the last Pratchett biography, he was most alive on the page. But I’m always happy to spend some time thinking about the Discworld.

I recently re-read Feet of Clay for perhaps the fifth time. It’s one of the City Watch series, and is about monarchy—there’s an old herald obsessed with bloodlines who wants to discover the lost heir to the throne of Ankh-Morpork, and at the same time the golems, magical beings who are regarded as non-sentient slaves, are trying to create their own King to liberate them from drudgery.

It’s an incredibly smart study of power, and it contains one of my favourite lines from a writer whose work is stuffed full of quotable lines: “Whoever had created humanity had left in a major design flaw. It was its tendency to bend at the knees.” I ended up quoting that line when I wrote an Atlantic piece in 2021 about Europe's ex-royals and the enduring appeal of monarch. Pratchett lines stay with you.

I first read Terry Pratchett as a teenager and, quarter of a century on, he is still in my brain all the time when I write. Not just his jokes and wordplay, but the way he saw the world—humane, not dogmatic, amused and amusing. He accepts that people are flawed but also thinks they are capable of extraordinary things: they are “the place where the Falling Angel meets the Rising Ape.”

One measure of how subtle and re-readable the books are is that the Reddit community dedicated to Pratchett is full of people announcing they have only just got a joke or a reference—maybe 20 or 30 years after first reading the book. I just saw a joke I had never got: Samuel Vimes gets served “love in a canoe coffee” in an Ankh-Morpork dive bar, i.e. it's “f***ing close to water.”

There's so much in Pratchett's novels that feels more relevant today than ever. He deals with eugenics and the idea of "lesser races" (Feet of Clay, Carpe Jugulum and Snuff); gun control (Men At Arms); sexism (Equal Rites, Monstrous Regiment); religious fundamentalism (Small Gods); and crumbling local government infrastructure (Going Postal, Making Money).

With Pratchett, the discourse always revolves around the idea that oh-ho-ho, isn't it funny that books with elves and wizards in them could address such big subjects. But genre fiction is often the best place to ask big questions or satirise contemporary society! Just look at Mick Herron's Slow Horses books, which do an incredible job of conjuring up the moth-eaten public realm of contemporary Britain under the cover of being a spy series. And actually, Jackson Lamb, with his dandruff and his farting and his implacable sense of justice, is a very Pratchettian character. So are Joyce and Elizabeth from Richard Osman's Thursday Murder Club trilogy: they’re basically Nanny Ogg and Granny Weatherwax solving crimes in a retirement village— and making subtle points about crooked developers, the toll of Alzheimers and the imaginative failure of writing off older people along the way.

Also, I might have said this before, but if you haven’t read the Thursday Murder Club or Slow Horses series, treat yourself! They are both excellent.

Quick Links

It’s a shame that Vivek Ramaswamy has such . . . ahem, unorthodox opinions about 9/11 etc etc etc, because otherwise I would be like, “vote for the guy who is willing to perform Lose Yourself in public” (Twitter).

It feels like articles about the menopause are following me around the internet. This one is about flooding so severe that women have needed blood transfusions (BBC).

Why do fans throw drinks at celebrities they love, or film themselves watching films? Eleanor Halls on performative fandom (Pass the Aux).

“Replying to a BBC email about this matter, Hannah Ingram-Moore said via email: ‘You are awful. It's a total lie.’ Six minutes later she added: ‘Apologies. That reply was for a scammer who has been creating havoc’.” Captain Tom’s family continue to deliver (BBC).

Freddie deBoer picks up something you will have noticed yourself from the images in this newsletter: Dall-E is not, at the moment, very good. Midjourney is better, and I know people who are having very positive experiences with coding using ChatGPT. But there is a fair bit of hype about.

See you next time!

Thanks particularly for the piece on Pratchett. You nail the multi-faceted nature of the post-Rincewind ones: comic fantasies with great plots, stuffed with literary and cultural allusions and frequently addressing important political or philosophical themes. In Wyrd Sisters there's a description of inspiration striking Hwel - ideas sleeting through his mind - that is a guess at how Shakespeare must have operated but which is also Pratchett describing himself I think. I find it hard to read the later books where the life and energy of the prose is increasingly affected by his illness. Anyway, buoyed by the link you make, maybe I should tackle Richard Osman's books too: always been put off, quite unfairly, by his slightly snippy demeanour on TV. Terry would have said you must separate the artist from their work, of course.

Jonathan Swift was an earlier practitioner of Mr Pratchett’s art, or Mr Pritchett’s cart if you are a fan of spellcheck.