The Bluestocking, vol 301: Anti-Woke Airline Food Comedy

Two plus eleven minus one, amazingly

Happy Friday!

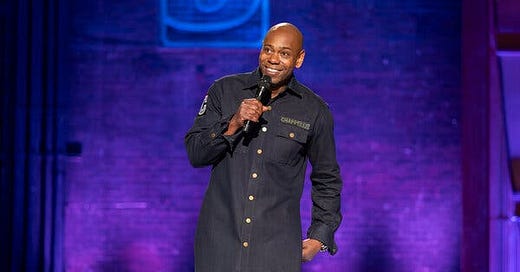

This week I’ve written something about Dave Chappelle and Ricky Gervais’s Netflix specials. After that come the usual links and tips.

Helen

PS. I’m doing a live event with Armando Iannucci on March 25. Tickets here.

The Real Problem With Anti-Woke Comedy

There has been a lot of Discourse lately about Ricky Gervais, Dave Chappelle and “anti-woke” comedy (here, here, here). How do we reconcile the purse-lipped disapproval from some quarters with the huge commercial success of these specials? Because those are two sides of the same coin, of course! Many people are making political judgements, rather than artistic ones, and using these cultural avatars to signal their political beliefs. It works out nicely for both sides: Everyone is lining up tribally and commenting on what Gervais and Chappelle represent. Of all the Discourse, I liked James Marriott’s column most because it engaged with the actual material of Armageddon, much of which was fairly antique stuff: isn’t the design of testicles bad?

Regular readers will know that the complete politicization of arts criticism is something that gets my goat. It manifests in a couple of ways: one, diversity/progressiveness has been repurposed as a marketing tool, and journalists play along with this, because it’s easier to write about the ideological content of an artwork for a mass audience than it is to appraise its technical details. And not just easier, but more likely to attract eyeballs. So any low-key project tends to get sold as smashing an identity based frontier—the first Korean-American romcom! A feminist reappraisal of Rose West!

Then, after the artwork is released, it fuels Discourse. You get a zillion thinkpieces on the “message” of Barbie—too much Ken? yass kween to America Ferrara’s inspiring patriarchy speech! yawn to America Ferrara’s paint-by-numbers patriarchy speech!—and relatively little on its artistic choices (e.g. the clever construction of Barbieland as a consistent world, such as having no water in the showers).

Here’s Adam Kotsko in the Atlantic on why “moralism is ruining cultural criticism”:

Every artwork is imagined to have a clear message; the portrayal of a given behavior or belief is an endorsement and a recommendation; consumption of artwork with a given message will directly result in the behaviors or beliefs portrayed. This is one of the few phenomena where the “both sides” cliché is true: Left-wing critics are just as likely to do this as their right-wing opponents. For every video of a right-wing provocateur like Ben Shapiro decrying the woke excesses of Barbie, there is a review praising the Mattel product tie-in as a feminist fable.

I’m with my colleague Yair Rosenberg, who sees this as a market issue. There’s a demand for this stuff, so people supply it. We’ve switched from a review culture (is this well directed? acted? written?) to an opinion culture (what does it say about the Yanamamo).

Also, he suggests, people banging out opinion on Barbie (guilty as charged) feel a bit bad that they’re not war correspondents, so they pretend that having an opinion on a new film is a vital weapon in the war on inequality and prejudice. “The deep-seated need to justify one’s own relevance is how we end up with cultural criticism that evaluates art as politics, rather than as art which also has political elements,” writes Rosenberg. “It’s how we get Playstation 5 reviews that scold people for owning one and being excited about it, because purportedly only privileged people do things like that.”

So much for the effect on journalism. What about the effect on the artists themselves? I watched Gervais’s Armageddon and Chappelle’s The Dreamer pretty much back to back, which I recommend because it shows you the problem here. Anti-wokeness is low-hanging fruit. This stuff is popular—because it’s funny and woke people are annoying—but it’s not edgy. Neither of these shows is particularly well-constructed or ground-breaking in comedic terms. Both men have done much better work elsewhere (Extras, After Life for Gervais; Charlie Murphy’s True Hollywood Stories, the racial draft etc for Chappelle). The joke about comedians whose success made them lazy used to be that their material would become “what’s the deal with airline food, hey?” The modern update of that is “what’s the deal with pronouns, hey?” Again, I’m not saying it can’t be made funny. It’s just a waste of talent.

Interesting, almost all discourse on these specials hinges on the question of who is being attacked in them. Are they punching down at vulnerable minorities, or punching up at censorious elites who won’t let us say things that are obviously true? Both of these framings accept the traditional progressive view that comedy should afflict the comfortable. It’s OK to be mean as long as the targets deserve it. Comedy hasn’t got nicer in the last decade, it’s just found new acceptable targets.

I’ve bracketed Gervais and Chappelle together not just because their Netflix specials came out at the same time, but because they are two of the best comedians working today and their styles have some overlap. Chappelle is more of a raconteur, but both of them crack themselves up, either for real or well faked, as part of their act. The impression is that they are recounting bizarre stories about the world and they can’t quite believe this is happening. Both of their acts rely on a high-status persona that is very hard to make work. Chappelle, being American, manages to pivot this superiority right at the end of The Dreamer into mawkish inspiration: isn’t it amazing that he is back in a city he used to play as a jobbing comedian who had to drag people from the street to be his audience? Ricky Gervais, being British, doesn’t bother. He just cackles on Twitter about how people keep attacking him and he’s wiping away the tears with his Emmys.

***

Here’s an example of the formulaic nature of this type of comedy. Both Armageddon and The Dreamer feature an extended riffing mocking someone disabled, in which the comic reversal is the comedian revealing that the disabled person is a bigot. So it’s now totally fine to mock their disability, hurrah!

In Chappelle’s show, the disabled person is supposedly annoyed that he’s now doing anti-wheelchair jokes when they came along for his anti-trans jokes. In Gervais’s show, he conjures up the image of being awful to a wheelchair-bound kid, only to reveal that the kid is a bigot and a paedo. In both cases, the men do a riff about how they promised their partners not to do an impression. (Gervais “promised Jane I wouldn’t do the voice.” Chappelle does do a little jerky arm movement, very like the one Trump used to mock a reporter, and says his wife will be upset.) If you’re a top-level comedian, and you end up doing material that is this similar to the material of another top-level comedian, you should ask yourself some serious questions about whether you’re phoning it in.

Chappelle also manages to get 10 minutes of material out of Chris Rock getting slapped at the Oscars—even though he admits that he developed this special on a tour with Chris Rock where Rock was also doing material on the slap. (A tour I went to see, because I’m enough of a fan of Dave Chappelle to go to the O2 on a Sunday.) That is peak Airline Food Comedy. Will Chris Rock now do a tight five on Dave Chappelle’s material on him? Where does it end?

Please, all of you, go to a mall or a McDonalds or call a customer-service helpline or anything that normal people do.

How A Script Doctor Found His Own Voice (New Yorker)

A prominent film producer told me, “For a long time, Scott Frank was the name people would bring up as a cautionary tale about the dangers of the rewrite system. This was someone who could be the next William Goldman, but he kept doing these weekly rewrites instead of his own original work.” When I asked Frank about that critique, he readily accepted it. “My career is probably best defined more as a failure of nerve than anything else,” he told me. “I used to book myself up three years in advance, out of fear.” Such anxiety can be a great motivator, but it can also amount to a life of safe choices.

By the time Frank reached his fifties, he was feeling a rising unease. There was no one eureka moment when he decided, like Flitcraft, to change his life. But, as Frank surveyed his career, he thought back to those childhood excursions in the Cessna with his father. For a good part of the past thirty years, he realized, he had just been “picking places to land.”

Patrick Radden Keefe profile of Scott Frank, one of Hollywood’s most prolific rewrite men—and by extension, an insiderish look at the business of making movies. Frank made his name by doing character work on films that would now not get made: standalone dramas, usually with the American equivalent of a 15 rating or above. His annoyance at the era of the superhero comes out in his script for Logan (my favourite of the X Men films, like a hairier King Lear): “In this flick, people will get hurt or killed when shit falls on them. . . . Should anyone in our story have the misfortune to fall off a roof or out a window, they won’t bounce. They will die.” Like many other writers, he has now moved to television: he adapted and directed The Queen’s Gambit.

PS. lol did this line resonate: “He began taking Zoloft for anxiety, a move that he had resisted for a long time, because he felt that fear might be integral to his creative process.”

Quick Links

“Two plus eleven minus one, amazingly (6).” A compilation of the most fun cryptic crossword clues (On Words and Up Words, Substack).

“Discussions of the ways in which Labour might under-perform are ten a penny right now. But there’s very little consideration of the opposite possibility: what would have to happen for Labour to win really big?” (Rob Ford, The Swingometer)

My respect for Richard Osman has increased further since discovering this archive clip of him talking to—well, politely confronting—Frankie Boyle over his approach to comedy in 2014. Doing spiky interviews is hard (most people want people to like them, and want to seem agreeable) and doubly so in front of an audience who might not be on your side.

“In many ways, it is less a political party than a company, with shareholders and an ever-growing number of customers. [Richard] Tice may be the leader of the party, but he is ultimately answerable to those shareholders — and the majority are owned by, you guessed it, Farage himself.” Tom McTague on the strange structure of Reform UK—which is basically set up as a Nigel Farage vehicle—and what the party wants, which is the defeat of the Tories at the next election, in order to secure electoral reform (Unherd).

Great line from showrunner Tony Tost on what he looks for when hiring: he wants people to be high performance and low maintenance (Practical Screenwriting). He also says something that I saw a fair bit in my days hiring young journalists: “Sometimes I think ambitious young people err in thinking that if they communicate how much the job will help their own personal ambitions, that this’ll somehow help them get hired.”

Via the Browser, home of excellent recommendations, Hakai magazine has a lovely story and pictures about a retiring lighthousekeeper.

Mr Bates vs The Post Office is a bloody good drama. Here’s the Private Eye special report on the Horizon saga, with the background to several of the cases in it (PDF). Richard Brooks, who has been writing about Horizon since 2011, was on the Private Eye podcast his week with me, Andy and Adam. I’m totally radicalised on this story, after reading/seeing what the sub-postmasters went through at the hands of the Post Office and Fujitsu. And I’m not the only one: this is the most righteously angry I’ve ever seen Ian, bringing up the fact that Paula Vennells got her CBE in 2019. I actually winced when Jake Berry tried to be snide to him about claiming to love the drama.

A personal plea: Could someone please write a good piece on the schism in the gender-critical movement so that I don’t have to? Thanks.

See you next time!

After rejecting Barbie film I eventually watched it, when streaming was cheap, and after seeing some heart warming interviews with Gerwig Robbie and Gosling and what fun they had making it and trusting their intelligence and good will. How the hardest thing was to get Mattel to accept the name of the main protagonist as ‘stereotypical Barbie’ that in itself was major, and lightly done. Even casting Ryan Gosling was so brilliant.. (with such a cool image re blade runner, drive etc.) : (Ken, shocked and confused in the Real World by Barbie telling builders that he didn’t have a penis assures them ‘I have all the genitals’ 😂. )

Yes there were clunky bits because it was aiming wide so couldn’t please everybody all the time. But bits of technical creative genius and with insight (eg how pregnant Barbie had been dumped by Mattel) it was gentle clever and funny.

Your main point about Chapell and Gervaise and why they think jokes about disabled people are necessary let alone funny, completely puzzled me too. There is a power of trans-activists that needs addressing but disabled people?

Oh and as for your last point, the division in the GC community? good luck with that although I too feel the fury of being dumped in a right wing camp because I believe that sex is real and gender a construct and reality is being traduced for the benefit of males and to the detriment of many groups of females. I think it’s time you did. The issue is who would publish it? The telegraph? The Mail? We need itv to do a drama.

I’ve got a lot of time for this critique (as I do most of what you write...) because fundamentally the politicisation of arts criticism is a feedback loop that rewards playing it safe, smug back patting and promotes moralising over entertainment.

Judging comedies by how morally righteous they are rewards all the kind of creative choices that nobody is going to choose to watch comedy for. Ted Lasso is a good example of a comedy that was rewarded for niceness and gentle humour, doubled down on all the things that critics encouraged, and ended with a series so filled with moral sermons that there was almost no space left for jokes. A good contrast is the Australian series Dead Loch, which tackles modern gender politics and a pretty eclectic range of representation but actually remembers to be funny - it’s a series that’s memorable because it’s hilarious, not because it’s morally insightful.

If I wanted to be told where my moral failings were, I’d try religion sooner than look for a Netfix comedy special that aligns with my values and belief systems.