The Bluestocking, vol 70: Imperfect art, ignored texts and irritating Facebook

Happy weekend!

I've had a Big Think this week, so feel free to skip that and go straight to the links. No one is judging you.

***

How do you deal with art which you love - but where you keep bumping on one thing about it, like your tongue suddenly hitting a ragged edge on a tooth? It's something I've been thinking about for a while, since watching The Twilight Zone at the Almeida. The play is clever, stylish and, almost entirely, full of safely dated monsters, like UFOs and strange dimensional portals and aliens wearing human skins.

And then in the second half, there's a 15-minute scene of a small community trying to come to terms with hearing the nuclear siren warning - just as the residents of Hawaii did a few days ago. One family is safely in their bunker, and the others hang around outside it, cajoling, threatening and begging to be let in - and arguing with each other over who is worthiest. It's one of the most incredible pieces of theatre I've seen in the last year, because suddenly everyone is having a nakedly honest conversation which strips away all their niceties, and we see the judgements of our worth which lie just below the surface. (Is a couple with a baby more deserving of salvation than a single person?)

This being America, race soon enters the conversation, culminating in an extraordinary exchange where a black couple are told, in so many words, "you didn't even choose to come here". The couple resist this, indicting America's legacy of slavery - which leads a white woman to say, with no idea of how terrible her words are until they leave her mouth, something like "This is why I don't like black people." (There's no script online, so forgive the imposition.) As well as the obvious meaning, she means that she'd rather spend her time with other white people, because then she doesn't have to confront - doesn't even have to think - about her complicity in an unjust system, and what she might have to give up to help erase it.

I suspect that's an extraordinarily common sentiment, even among Ye Blessed Woke Of Twitter. (I particularly think this since tweeting about the Presidents Club dinner this week, asking how many of my male peers have been to an event at a gentleman's club event recently without even thinking about it... suddenly, when the conversation switched from Everyone Bash the Bankers to Oh, Might I Have Done Something A Bit Off?, silence reigned.)

Anyway, I mention the Washburn play because - as I said on Saturday Review at the time - that section is so brilliant, so painful, and so relevant . . . that it not only transcended the rest of the play, it obliterated it. Which put me in the strange position of thinking that the beauty of that scene ruins The Twilight Zone. I had a similar experience last night at Mary Stuart, where one scene - a sexually charged encounter between Elizabeth I and the Earl of Leicester - really doesn't work for me. The physicality is too much; they grapple with each other like wrestlers, and the guy playing Leicester goes extremely red in the face with the sheer effort of hoisting Elizabeth to his shoulders. I can't help thinking about what the (otherwise startlingly beautiful) play would be like without it.

But this is the thing I don't know: am I wrong? Would both plays be less interesting - would they stay with me less - if you sanded off the awkward, jarring elements? "Perfection lacks texture," wrote Roxane Gay, and I wonder if there's a special kind of affection you feel for something you feel is not quite finished, untouchable, unimprovable. You can love a human, after all; you only worship a saint. Maybe it's the same with art.

So I'm interested - is there a play, or painting, or novel, you love except for one thing that you long to "fix"? And how does that affect your memories of it? Hit reply and let me know.

Helen

How It Became Normal To Ignore Texts and Emails

People don’t need fancy technology to ignore each other, of course: It takes just as little effort to avoid responding to a letter, or a voicemail, or not to answer the door when the Girl Scouts come knocking. As Naomi Baron, a linguist at American University who studies language and technology, puts it, “We’ve dissed people in lots of formats before.” But what’s different now, she says, is that “media that are in principle asynchronous increasingly function as if they are synchronous.”

The result is the sense that everyone could get back to you immediately, if they wanted to—and the anxiety that follows when they don’t. But the paradox of this age of communication is that this anxiety is the price of convenience. People are happy to make the trade to gain the ability to respond whenever they feel like it.

... a headline to which my riposte is, "not in this house it didn't, sonny". If someone doesn't reply to my text within 24 hours, I assume they're dead. And WhatsApp has just made this worse, because you can SEE that someone has been online, but they have chosen not to read/respond to you. Oh god, you think, she's angry with me. Or: that joke was definitely too near the bone, and they're all trying to find a polite way to move on without acknowledging it.

If only there was a modern Woody Allen to write a great screenplay about all this, and then not marry their adopted daughter.

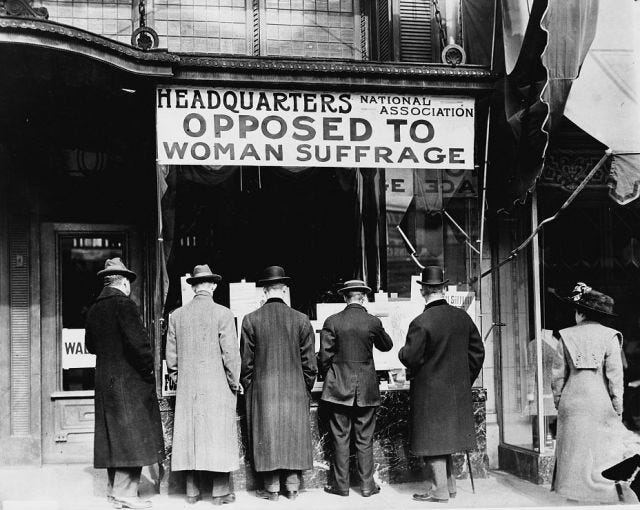

After the Suffragettes: how women stormed Westminster

To the suffragettes and suffragists, the House of Commons was a physical reminder of the structures of power from which they were excluded. As well as the broom cupboard, the building bears other marks of their protests. A statue of Viscount Falkland in St Stephen’s Hall has a broken spur from where an otherwise obscure activist called Marjory Humes chained herself to it on 27 April 1909.

When I visit, a group of school pupils are having the story explained to them, with the Commons guide trying to outline why so many women felt violence was a necessary answer to their predicament. (Earlier, trying to find the right statue, I asked an attendant if this was the one with the mangled spur. “Yes, and a 10-year-old child broke off the sword two months ago,” he replied. “The teacher was like, meh.” He shrugged, eloquently.)

I wrote about how the suffrage campaign left its mark on Parliament's buildings - and the challenges facing women in politics today.

Facebook Begins Its Downward Spiral

Stories about Facebook’s ruthlessness are legend in Silicon Valley, New York, and Hollywood. The company has behaved as bullies often do when they are vying for global dominance—slurping the lifeblood out of its competitors (as it did most recently with Snap, after C.E.O. Evan Spiegel also rebuffed Zuckerberg’s acquisition attempt), blatantly copying key features (as it did with Snapchat’s Stories), taking ideas (remember those Winklevoss twins?), and poaching senior executives (Facebook is crawling with former Twitter, Google, and Apple personnel). Zuckerberg may look aloof, but there are stories of him giving rousing Braveheart-esque speeches to employees, sometimes in Latin.

Nick Bilton of Vanity Fair, who wrote the story of Twitter's founding, is kinda done with Facebook. Among the many insights here is the killer fact that Facebook, to many people, no longer feels fun. It feels like another chore - put the bins out, empty the dishwasher, let everyone know I'm back from holiday - or a bad habit, where you listlessly scroll through other people's updates, but can't be bothered to post one of your own. Another great revelation in this piece, apart from the Latin Zuck speeches - Facebook knows how to track you and your friends through the dust on your phone's camera lens.

Who are you calling a second-wave feminist?

On the internet, arguments unfold at light speed, and people are quick to lump a bunch of different things together under some catchy label. When young women toss off insults at second-wave feminists, they're often speaking in code about something deeper: a resentment of their forebears. Women have trouble with their mothers.

But most of us actually know something of our mothers. The same does not apply to the mothers of modern feminism.

The #MeToo backlash (from people like Catherine Deneuve) has spawned a backbacklash, among younger feminists who are too quick to damn everyone over the age of 35 as a Grandma Who Needs to Log Off. To do this, some are invoking the Second Wave, without apparently having any real insight into who was in the second wave, what it did, and what its actual shortcomings were. This is a good riposte.

Quick links:

- Incredible thread of images from the abandoned offices of the Coventry Evening Telegraph. If you want to see the decline of local journalism, here it is.

- The FT's work advice is "do less and obsess". I'm failing at the former, but doing a bang up job of the latter.

- The phenomenon of the "work wife" - why powerful men need to surround themselves with women whose jobs blur the personal/professional boundary.

See you next time!