Matthew Perry, the best Friend I never knew

The man who made Chandler, when Chandler made me

Programming note: sometimes, a person makes such an impression on your life that you have to mark their death. So here’s something about Matthew Perry, the most important man in my teenage life.

Helen

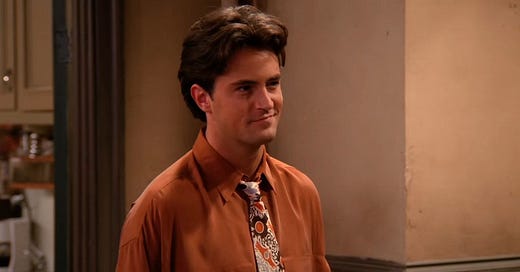

Chandler was so clearly my favorite Friend that there was no need for a contest. Joey was handsome, Ross was a dork, but Chandler was normal—or rather, I realize now, weird in the same ways I was. He was sarcastic, insecure, anxious. He was the patron saint of self-sabotagers: “What if I never find somebody? Or even worse, what if I’ve already found her and I dumped her because she pronounces it ‘supposeably’?” So many of Chandler’s best jokes—remember his horror at Joey and their matching bracelets “from the Liberace house of crap”?—came from pushing away the threat of genuine emotions. He was the Friend who found it hardest to have friends, someone who had to stop themselves firing out the kind of jokes designed to keep other people at bay.

We have Matthew Perry to thank for that. I woke up this morning to discover from a text from a friend that he had died—at 54, no age at all, in the jacuzzi at his home in Los Angeles. His last Instagram post a week ago showed him in the water there, linking it to a character he had recently created—“Mattman,” like Batman.

We don’t yet know whether Perry’s death was related to the decades of drug addiction about which he wrote so honestly, or the health problems he suffered as a result. I first realised something was wrong with him in 1997, although I didn’t know what. In “The One With The Hypnosis Tape,” Monica dates a tech billionaire, Ross and Joey try to warn Phoebe’s brother off marrying his teacher, and Chandler tries to quit smoking. Unfortunately, he uses Rachel’s hypnosis tape, which tells him that he is “a strong confident woman who does not need to smoke.” He duly wanders through his apartment to the bathroom in a towel, treating it like a spa rather than a room used by two men to take a dump.

Perry is on screen like this for less a minute, but it’s enough to notice that his arms are bony and his chest is hollow. In the era before stealth Ozempic, actorly weight struggles were not rare—one of the Desperate Housewives confessed that “not to eat is a constant struggle” and we all somehow accepted that as normal. But we now know that Perry was so thin because he had become addicted to Vicodin, which he was legally prescribed for a back injury and found impossible to quit.

Perry was an early, high profile example of America’s painkiller epidemic, and proof that it wasn’t restricted to dropouts and deadbeats. He had started with Budweiser and wine at 14, and eventually progressed to everything except heroin. He spent an estimated $9m getting clean. In time, his addiction led to an exploded colon, the loss of his front teeth and two decades in rehab facilities and sobriety programmes. In his memoir, he claims to have been so blitzed that he didn’t remember filming three seasons of Friends—the same ones that I loved as a teenager with a force so great I would almost hug the television, sitting a bare foot away from it, guarding it from anyone else in my family who might have thoughts of watching something else.

Chandler was everything I wanted in a boyfriend—smart, funny, emotionally unavailable—and Matthew Perry’s embodiment of him surely shaped the sexuality of a generation. Later, I realized that I didn’t want to date him as much as be him. The other Friends might have struggled to find work (see: Monica’s “mockolate” recipes, Joey’s porn cameo and Rachel’s waitressing) but Chandler had the ultimate 90s problem, in the form of a job that paid the bills but achieved absolutely nothing. Perry’s performance lifted a motif of the decade—the sterile life of the office drone, also found in Fight Club and The Matrix—into exquisite comedy. He bantered by the water cooler. He got sent to Tulsa. He knew that nothing he did mattered, and that his real life was waiting for him at Central Perk.

In the era before home broadband and streaming services, Friends was incandescently popular, partly because it was so good and partly because there was, frankly, little else to do in my small city in England if you were 14 on a Friday night in 1997. When I reach back into my adolescence, Perry is there—drinking beer in his reclining chair, making that strangled duck sound he used to indicate displeasure, declaring that “. . . and I just won a million dollars!”

The show went on so long, and at such a consistent pitch of excellence, that its characters couldn’t help drawing on the actors who played them. But when you read the scripts, it’s mind blowing how spare the lines sometimes are compared with what ended up on screen. In one of my favorite episodes, “The One Where No One’s Ready,” Joey and Chandler go to war over the possession of an armchair. Chandler’s line as he hovers next to Joey, hand in his face — “not touching, can’t get mad” — depends entirely on Perry’s delivery.

Is it too much to see Chandler’s endless on-off relationship with Janice as a metaphor for addiction? Maybe. But Perry lent real bittersweetness to the plotline of Chandler’s cross-dressing dad, the more so once you understand how difficult his relationship with his own father was.

That plotline now deemed intensely problematic by people who don’t understand that anything your parents do is achingly embarrassing, no matter how right-on you are—Who wouldn’t cringe at one of their parents having an affair with a pool boy and becoming a drag queen, even if they would happily do those things themselves? But in the episode where Monica drags Chandler to Vegas to ask his dad to their wedding, during the drag show, right before he sings It’s Raining Men, Perry invests the moment with real pathos, the adult emotions of hurt and forgiveness and benediction.

The sheer ubiquity of Friends made the six cast members famous to a crippling degree. Fame freezes, and the greater the fame, the deeper the chill.

The problem with the Friends was that they couldn’t grow up. We wanted them to remain twentysomethings—and so did the show’s writers. In one episode, Rachel has a revelation on her 30th birthday that she should have already met the father of her children, according to her life plan. Instead, she is dating the unsuitable Tag. Joey more straightforwardly cries out: “Why God, why? We had a deal.”

Friends had to end when it did because your thirties are when life’s infinite possibility curdles into compromise; when you understand, as George Orwell once wrote, that “any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats”. (Orwell would have approved of Perry’s brutally honest memoir, since he believed that “autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying.”)

But the Friends themselves, including Matthew Perry, had to go on. This is a burden we place on celebrities. Britney Spears writes in her recent memoir that people wanted her to be 17 for ever. What will Taylor Swift be at 40, singing about homecoming and proms begins to seem odd rather than nostalgic? You wouldn’t wish early success on your worst enemy; it’s the same as cursing them to know for most of their life that their golden days are already gone.

***

When the cast of Friends reunited in 2021, it generated two big online discussions. The first was wholesome: Matt LeBlanc, once a floppy haired James Dean-esque charmer, had grown into your favorite “Irish uncle.” Maybe it was the relative lack of fillers, but he seemed . . . relaxed. He had moved up a generation, and it suited him. You wanted to be around him, this former lothario turned into a twinkly, wise presence. “Matt LeBlanc looks like the Dad on Christmas that is happy to see you open your gifts even though he doesn’t know what any of them are cos your Mum got them all,” read one tweet. “Matt LeBlanc sat there like your dad watching your first boyfriend that he dislikes trying & failing to fix the home PC,” read another.

The second discussion was less happy: god, poor Matthew Perry. He seemed jittery and absent, and if that wasn’t a big enough clue that he wasn’t well, then there was the mixture of tension and protectiveness from the others that you could sense every time he spoke. Loving an addict is not a simple sensation: they won’t stay helpless and pitiable, but are just as often petty, mean and immature. Perry’s book is commendably upfront about these qualities. At one point during the recording of Friends, Jennifer Aniston tells him that the others know he has started drinking again because “we can smell it.” Perry writes: “The plural ‘we’ hits me like a sledgehammer.”

I met Matthew Perry once, in the early 2000s. He came to Oxford, my university, to speak at the Union. Somewhere there will be an official picture of us together, but this was before the era of the smartphone, when photographs required a trip to a pharmacy to be developed, so I’ve never seen it. During my own twenties, I used to joke that meeting Perry was the day my adolescence ended: that I said hello to this icon of my teenage years, this idol who had meant more to me than anyone I had dated during that time, who had left his fingerprints in my clay for life . . . and discovered that he was just a man. Sarcastic, insecure, anxious. Perry walked into the Union chamber, looked at the huge crowd and said, “Could there be any more people here?”

He gave us what we wanted. . . and I hated it.

Since then, I have been cautious of fame—if not actively hostile to it. Celebrity is a product of narcissism: ours, not theirs. We want to place ourselves in relation to something bigger: we are Friends fans, Swifties, K-pop stans, the Beyhive. We measure out our lives, not in coffee spoons, but pop culture moments. Do you remember when Monica was hiding in Chandler’s bed when Ross came in? Do you remember when Ellen came out? Do you remember when Mulder and Scully finally kissed? We see echoes of ourselves—our dating disasters, our dead-end jobs, our failures that transform into jokes in the telling. I am who I am today because back then, I wanted to be Chandler. The cruel twist is the man who gave me that gift never got to enjoy the rewards of success himself—he didn’t even remember making those episodes.

Matthew Perry was a transcendentally gifted comic performer who helped me grow up, even as he lived in the shadow of his own eternal twenties. I wish he had enjoyed his life more. I wish he had more years. I wish he could have grown old, surrounded by people who loved him.

Your regular Bluestocking returns on Friday. If you were forwarded this email, you can subscribe here.

![PHOTOS] 'Friends' 10 Best Streaming Episodes — HBO Max – TVLine PHOTOS] 'Friends' 10 Best Streaming Episodes — HBO Max – TVLine](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!oFrr!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9fbdbde2-8f53-4630-a4c1-9c4bc7282f9b_799x541.png)

His death was announced only a few hours ago and you've already managed to distill everything I instinctively knew - but had never articulated - about Friends and fame and celebrity crushes into a couple of thousand perfectly-chosen words. Thank you for your essay - and for your eloquence.

So beautifully written, this has put into words the sad feeling that’s been knocking around my brain all morning.