Happy Friday!

Something a little different for you this week — a short extract from The Genius Myth, which was published in the UK yesterday. (From what I can tell, it’s selling best on audiobook, which bolsters my belief that we prefer to watch and listen rather than read these days.)

The extract below is about the psychologist Hans Eysenck, who himself wrote a book attempting to define the concept of genius1 and very much saw himself as one. This story comes from Part One of the book, which traces the history of genius through the biographies of Renaissance artists, the birth of the “tortured artist” trope in the Romantic period, and on to the nineteenth and twentieth century obsession with taxonomy and IQ. Part Two looks at various myths of genius, and Part Three is about their dominant modern form—the tech innovator.

Helen

The name of Hans Eysenck is little remembered now, but when he died in 1997, he was the third most-cited social scientist, behind Marx and Freud. (He had published seventy-five books and 1,600 journal articles.) In 2002, the American Psychological Association named him the thirteenth most eminent psychologist of the twentieth century, ahead of Carl Jung, Solomon Asch and Ivan Pavlov.

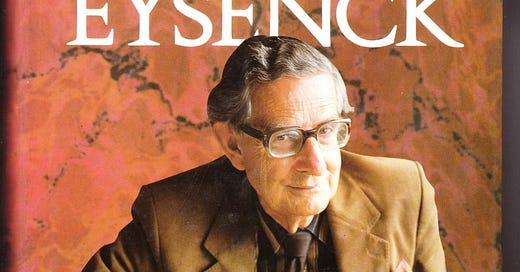

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, Eysenck was the leading light of personality studies, arguing that our inner selves can be graded on introversion, neuroticism and (later) psychopathy. Because he died just a few days after Diana, Princess of Wales, the Guardian obituary described him as the People’s Psychologist. His autobiography is called Rebel with a Cause.

Unfortunately, though, there is an unanswered question hovering over his work on intelligence, personality—and genius. A very simple one.

Is any of it true?

*

As an undergraduate, Hans Eysenck studied under the pioneering psychologist Cyril Burt. When his mentor was accused of faking some of his data, Eysenck defended him. ‘Scientists have extremely high motivation to succeed in discovering the truth; their finest and most original discoveries are rejected by the vulgar mediocrities filling the ranks of orthodoxy,’ he wrote. ‘They are convinced that they have found the right answer . . . The figures do not quite fit, so why not fudge them a little but to confound the infidels and unbelievers? Usually the genius is right, of course (if he were not, we should not regard him as a genius) and we may in retrospect excuse his childish games, but clearly this cannot be regarded as license for non-geniuses who foist their absurd beliefs on us.’

I am oddly grateful to Eysenck for this passage, a phenomenal example of ‘saying the quiet part out loud’. A genius does not have to play by the rules in pursuit of a great discovery. Hang on, though. What if his great discovery turns out to be garbage, perhaps because he bent the rules? Ah, then he wasn’t a genius after all.

This kind of circular logic ought to disqualify a scientist from being taken seriously. Yet in 1995, Eysenck published a book called Genius, which makes an astonishing series of claims, all supposedly backed by scientific research. Again, he was blasé about outright fraud, arguing that ‘many famous scientists . . . deviated significantly from the paths of righteousness, including Ptolemy, Galileo, Newton, Dalton, Mendel . . . ideology may cause fraud, and it also seems to influence how the accusation is treated’.

Eysenck believed that geniuses needed a particular combination of psychological traits, scoring high on both psychoticism (‘an inclination not to limit one’s associations to relevant ideas, memories, images etc’) and ego strength. He made airy, assured judgements: the physicist Stephen Hawking was ‘first-rate, but no genius’. And he dismissed the idea that women are just as brilliant as men:

‘Creativity, particularly at the highest level, is closely related to gender; almost without exception, genius is only found in males (for whatever reason!). Illustrations abound. There are no women among Roe’s eminent scientists, and very few in American Men of Science, or among members of the Royal Society; none on a list of the leading mathematicians, and none would be found among the 100 best-known sculptors, painters or dramatists.’

Did you inhale sharply at this? I did. Why are there no women in the 1906 compendium called American Men of Science? It’s a three-pipe problem. As for Eysenck claiming he could find no notable women in the Royal Society – well, give them a chance. The great scientific club was founded in 1660 but refused to grant women membership until 1945. Men had a three-century head start. Hertha Ayrton, the great electrical engineer, won the Hughes Medal from the Royal Society in 1906 for her work on arc lights, but was still barred from becoming a Fellow2.

Other great female physicists had to work outside the system, too. The Austrian-American actress Hedy Lamarr had an intelligence every bit as eclectic as that of many of the great male pioneers of the Enlightenment, and was similarly self-taught. She tinkered with a tablet that would carbonate drinks, and suggested improvements to traffic lights, before inventing a frequency-hopping system to prevent torpedoes being jammed. (It was eventually adopted by the US Navy.) And she played Delilah for Louis B. Mayer, never mind marrying six times.

Reading Hans Eysenck’s Genius, the uncomfortable questions only become more pressing. On page 162, noting clusters of scientific innovation throughout history, Eysenck speculated that perhaps role models acted as mentors and inspirations to an entire generation that followed them, causing a flowering of discovery. ‘An alternative, or possibly additional cause, is the postulation of extraterrestrial factors,’ he added.

Sorry?

There follow six pages on sunspots, and the possible correlation of solar activity and fertile intellectual periods like the Renaissance in Europe and the Middle Ages in China. Eysenck wonders if magnetic storms and their ‘very energetic emissions may have some influence on biological organisms, although we would of course demand exceptionally cogent evidence’.

He concludes the chapter by suggesting that there is enough data for a ‘rough portrait’ of the genius. ‘Clearly, he should be male, of middle or upper-middle parentage, and preferably come from a Jewish background,’ Eysenck writes. ‘He should receive intellectual stimulation at home, but ought to lose one parent before the age of 10. He should be born in February, and die at 30 or 90, but on no account at 60! He should so arrange it that at the time of his maximum creative powers (between 35 and 45, or even younger for mathematicians and poets) there should be a minimum of solar activity.’ Oh, and he should have gout – a painful condition which affects the joints, caused by a build-up of uric acid. After all, ‘uric acid has been found to be quite highly correlated with achievement and productivity, although only slightly with IQ’.

There’s no hint in Eysenck’s taxonomy that correlation and causation are tricky beasts. Gout might well be correlated with professional achievement, but only because the condition is more common in middle-aged men with enough money to eat a lot of rich food. The kind of people with gout are also the kind of people who are most likely to have done well in their careers. However, you can’t scoff pints of beer and buckets of shellfish and expect it to cause a rise in your productivity. If you’re hunting for genius, you should look elsewhere.

What is this guy smoking, I thought to myself. And then it got worse, because then I heard about his cancer research.

*

Anthony Pelosi is a cheerful soul, and he has spent thirty years trying to destroy Hans Eysenck’s reputation. When I read Eysenck’s verdict on his mentor Cyril Burt out loud to him, about how geniuses were allowed to make stuff up, Pelosi laughed. ‘I don’t think he was talking about Burt there at the time, really. He was really talking about himself.’

In the early 1990s, Pelosi was a young psychiatrist, and he read Eysenck’s famous research on the links between personality and heart disease. The older man was claiming that different personality types were more likely to suffer from particular ailments: there was a ‘heart disease-prone’ personality and a ‘cancer-prone’ personality. (The latter led him to question the scientific consensus that smoking caused lung cancer. He concluded that smoking ‘does not kill’.) In one paper, Eysenck and his collaborator Ronald Grossarth-Maticek claimed to have treated extreme high blood pressure successfully with psychotherapy. They claimed the trial worked but, Pelosi told me, ‘you look at the tables, you’re having huge death rates down the line’.

Feeling that such experiments were unethical – it seemed that the subjects had been exposed to unproven treatments for their conditions, instead of giving them safe, tested alternatives – Pelosi read on. As he did so, he came to a more startling conclusion. He no longer believed the research was unethical. He believed the data was impossible.

In 1992, while Eysenck was still alive, Pelosi and his co-author Louis Appleby published their first article in the British Medical Journal on the psychologist’s claims about heart disease and cancer. These were very carefully worded, he says, because the lawyers ‘wouldn’t allow us to say this is fraudulent’. (‘These long awaited papers contain some of the most remarkable claims ever to appear in a refereed scientific journal,’ they write; a sentence which can very much be read two ways.)

Pelosi made formal complaints to professional bodies, and tried to interest the British Psychological Society in the issue. When they showed little interest, he says that he told them: ‘Someday this will come back and bite the British Psychological Society in the bottom. It will bite lots of people in the bum.’ He spoke to a journal editor, who worried that academic disputes were common, and that such serious accusations would require intensive legal support. Throughout the 1990s, however, other scientists came forward to question Eysenck’s data on personality types. In 1995, the year Eysenck published his book on genius, at least twenty papers questioned his findings. But neither his university nor the professional bodies acted. Nothing happened, either, when leaked documents revealed a year later that he had received £800,000 in research funding from tobacco companies34.

Eysenck died the following year, in 1997. At his death he was an eminent but controversial man: there are five portraits of him held in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. In 2001, an exhibition on the last one hundred years in psychology at London’s Science Museum staged a replica of his personality testing lab. As an example, a single one of his articles – a 1985 paper on Personality and Individual Differences, offering a modified version of the Eysenck Personality Test – has been cited more than 3,000 times. Others have even more citations.

But like many other self-styled geniuses I have written about, he was also an attention-seeker and a hate figure. He was interviewed in Penthouse. He dabbled in research on astrology. He was assaulted on stage by a student for his views on IQ and race. (He believed that the environment was not solely to blame for racial differences in IQ.) His work on IQ gave succour to the National Front and other racist groups – although he always denied holding racist views himself, and even his most critical biographer Rod Buchanan states that ‘he was too self-absorbed, too preoccupied with his own aspirations as a great scientist to harbor specific political aims.’

He accused anyone who complained about his work of being politically motivated: ‘the scattered troops’ of the left, trying to censor a maverick thinker. Hans Eysenck was deeply invested in all the mythology of genius. He was Galileo uttering forbidden truths; he was Cyril Burt pursuing unorthodox methods in pursuit of nobler goals; he was an intellectual titan among lesser mortals with middling IQs.

In 2016, long after the first questions had been raised over Eysenck’s work, a psychologist called Philip Corr wrote a defence of him for the Times Higher Education magazine. It was headlined: ‘Sometimes you need a pariah’. Corr regrets that if Eysenck were working today, he would be consumed by Twitterstorms and cancelled for wrongthink. ‘Even if he had managed to secure an academic position in the first place, he certainly wouldn’t have landed a chair. That would have saved a few feathers from being ruffled, but would it really have been in the long-term interests of science?’

It’s a question worth pondering, since it posits the genius – Eysenck, in this case – as unique and irreplaceable.

But is that really the bargain – that peddling questionable data and supplying ammunition for the far right is a price worth paying for the furtherance of psychology as an academic discipline? Must we say: oh, you want Freudian psychoanalysis debunked? Then you have to sign off all that guff about cancer-prone personalities, too.

*

In 2019, Anthony Pelosi finally got an article published, alongside an open letter to King’s College, London, saying ‘there is clearly evidence that this must be investigated’. The letter listed sixty-one questionable articles – twenty-six jointly published by Eysenck and his collaborator Ronald Grossarth-Maticek, ‘and the rest single-authored by this man who considers himself a genius.’

In a rebuttal – on a website that has since been deleted – Grossarth-Maticek denied any allegations of unethical conduct or that he had engaged in research fraud, saying that he was open about his approach to data collection, which used ‘the most effective method of evidence in the history of psychology and epidemiology’. He characterised the requests for retractions as a witch-hunt, writing: ‘Doesn’t this procedure remind us of the fascist book burning? The Nazis wanted to make disagreeable authors disappear from literature so that they could no longer be quoted.’5 When King’s College agreed to investigate, Grossarth-Maticek sent a letter to its president, arguing that the university was ‘a powerful representative of British and Jewish psychology. All of them don’t want the little German Grossarth to dominate the scientific world stage.’

When King’s College eventually published its conclusions on its divisive star, the university declared Eysenck’s twenty-six co-authored papers ‘unsafe’. One of them is the paper that started Anthony Pelosi on his quest, published in Behaviour Research and Therapy – a journal Eysenck himself founded. More than a dozen further papers have since been retracted by the journals involved, going back to 1946, and more than seventy have ‘expressions of concern’ attached to them. The corrections and retractions relate to Eysenck’s observational work on the factors which lead to cancer, and his interventions to curb the disease.

But where does that leave Eysenck’s work on IQ, and on genius – his implicit contention that white men held the best jobs and made the biggest breakthroughs because of their superior intellect and personalities? There has been no inquiry into this portion of Eysenck’s work, and there is no suggestion of one.

Pelosi believes that Eysenck had a ‘quasi-religious’ belief in his findings, and he lays some of the blame on the milieu that surrounded the celebrated academic. ‘We have a self selection of these guys as they gather around each other,’ he told me. ‘A lot of his own pupils were egging him on: “You are a genius, Hans.”’ As an academic superstar, Eysenck was able to dictate papers to his secretary and send them out to be published. He ranged far beyond a narrow specialism where an individual researcher might be able to be confident about their findings, becoming a universal smart person, a public intellectual. He wasn’t visited by genius; he was a genius. His view of IQ fed into a particular mythology, which justified a particular view of the world, and encouraged him to adopt a particular view of himself. He played a genius on television. Even his wife Sybil bought into the mythology. Her unpublished and unfinished autobiography has an astonishing title: I Married a Genius.

Telling me this, Pelosi breaks into laughter again, a full- throated Scottish roar. ‘I think my wife would like to write something . . . I Married a Daftie.’

This is an adapted extract from The Genius Myth, which came out on June 17 (US) and June 19 (UK). The nice people at Bookshop.org have given me a 10 percent discount code: genius10. Enter that at checkout for a cheaper copy.

4.2 on Goodreads, hilariously.

Updated June 21, because I originally wrote “Academy” here instead of “Society”

Eysenck’s university, King’s College London, investigated in 2019. That year, the British Psychological Society printed a call to investigate Eysenck’s work in its in-house magazine, but countered it with an official statement that concluded: ‘The conduct of research lies with the academic institution which oversees the work carried out by its academics and we welcomed the investigation into this research carried out by King’s College, London.’

When asked about this in a Channel 4 documentary, Eysenck said: ‘I’m not sure of any of this . . . we get a lot of research money. As long as somebody pays for the research I don’t care who it is.’ Quoted in Peter Pringle, ‘Eysenck took £800,000 tobacco funds’, Independent, 31 October 1996.

The rebuttal also insisted that the younger man had not been manipulated by Eysenck, and their relationship was ‘equal and very creative’. Archived here.

Thank you for this book -I look forward to reading it for all the ways it will vindicate my *longstanding view that this man was a scandalous charlatan -definitely not a genius! *When I was a first year as a young but mature enough psychology student to question things,(1965/6 this man came to give a lecture at the university and also a Q&A talk in the Psychology department. Up close from the front row he looked surprisingly disreputable but worse - after looking down at me and several other keen but coincidentally blonde (yes that too) minority of young women - he spoke directly to us saying that he was pleased to be there -but couldn’t understand why we were there… we could stay if we wanted to but.. Our dear Prof didn’t know what he meant but I did and shocked at the blatant insult I walked out and the others followed. Emperors knew clothes it may have been but in later studies it was even more obvious that his methods and claims were unsupportable and his views obnoxious.

I never cited his work and would always explain to my students later my reasons for this and how they should not do so nor use his inventories but to question and look further and better. In my Adult Education teaching the hidden scandal of Eysenck and his influence was a great example for many wide ranging topics of discussion (political social historical, geographical critical feminist etc) relating to psychological research and it’s influence. I’m glad we can now call time on all his dangerous nonsense!

Great extract and very enjoyable read. I lost count of the times that I mentally cried, "What! No way!" I'll be ordering a copy of The Genius Myth to be further entertained and infuriated.

Cheers.