Happy Friday!

A special edition as I had a new theory to share / a rant to get off my chest.

Helen

The Ant Mill Theory of Social Media

I’m having a wee break from Twitter—since I don’t need to be immersed in the news while writing this book—and it’s reconfirmed my belief that its existence has wildly deformed the Take Industry.

This week, browsing the news sites I regularly read, I saw two pieces in quick succession about how Nazanin Zaghari Ratcliffe didn’t need to express gratitude to Britain for her release from an Iranian prison. No one would expect gratitude of a man, said one. This is because she isn’t white, said another. Then Jeremy Hunt weighed in to say the same.

But here’s the thing— I had no idea who was expecting Nazanin to be grateful. It was just not a sentiment that had made it through to me.

Further investigation revealed that she expressed anger at her post-release press conference that it had taken so long, after which “some people suggested online she should instead be grateful” (Times).

The Guardian rounded up criticism from UKIP funder Arron Banks, former Conservative MEP David Bannerman, and some London Assembly Member you’ve never heard of (sorry, Susan Hall), as well as “another poster” who tweeted: “See #ungrateful trending, after [£]400m spent to release her she takes aim at the government in a very polished vile manner.

So that’s who we’re all arguing with? Arron Banks and “some people online”?

As a brief aside, I take the idea that “#ungrateful” trending suggests anything meaningful about Britain with a pinch of salt. First off because most people aren’t on Twitter, and the self-selected group who are skew heavily towards the shouty and insane. Also, quite often when you click on a trending hashtag, the most liked tweets are those going “Why is #dieJKRowling trending??? That’s appalling”. Equally often, the hashtag is full of people tweeting “I’m so confused, why is #PutinIsAMelon trending??

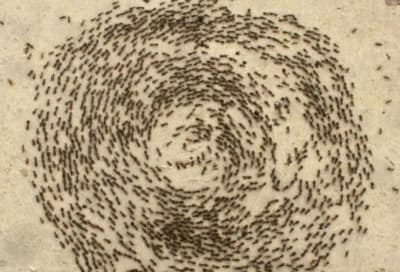

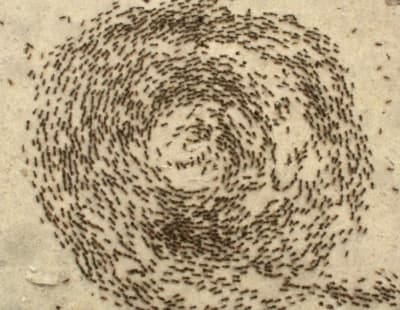

The Nazanin backlash-to-nothing reminded me of a horrible but fascinating natural phenomenon.

The ant mill.

Army ants are blind, and so they follow trails by pheromones. This is a great system right up until the pheromone tracks cross, at which point the ants enter a death spiral, marching round and round until they die of exhaustion.

Twitter is journalism’s ant mill. It allows Arron Banks (72.5k followers) to hijack the attention of liberal tweeters, and then liberal columnists, from the comfort of his own home. (There are figures with similar abilities on the left, so this phenomenon happens in reverse, too.) For the tweeters, there is an opportunity to signal their own position—this is sexism, which I’m against/this is racism, which I’m against—which is then picked up by columnists, who (I speak from experience) are always desperate for topics, particularly at times when one subject is otherwise dominating the news.

Marina Hyde’s column gets a pass here, because it draws links back to the Stormzy/Afua Hirsch gratitude discourse, to demonstrate that there’s a repeated pattern of non-white Britons being expected not to criticise Britain. Her column works because she’s Marina Goddamn Hyde, that’s why; but also because she can find high profile named people who have previously expressed similar views.

But in this case, even she can only plead in evidence for anti-Nazanin sentiment the #sendherback hashtag (with the concession that it was “bolstered” by people expressing outrage) and some guy called Jason calling in to Nick Ferrari. To put it mildly, if we wrote columns every time someone called into LBC with a bad opinion, there would be no time for lunch.

There’s nothing wrong, in itself, with rebutting the massed troops of Arron Banks, three tweeters with bulldogs as avatars and five BTL commenters called True Born Englishman. But here’s another change social media has wrought: that rebuttal used to be confined to the pages of a newspaper, and only really dweebs and journalists (big overlap) read more than one newspaper. But now writers are posting their headlines to Twitter and Instagram, their publications are promoting the piece online, and these reaction takes are being injected back into social media, where the pheromone trail crosses again.

That’s because people who would have ignored one article on the subject now they feel they’re being bombarded with “Nazanin doesn’t owe you gratitude” takes. And they think “well, sure, but Britain did pay £400m—” before realising that expressing any ambivalence would bring a huge pile-on, and then they think “cancel culture is real” but also know they shouldn’t say that either . . . or they flip completely and think “stop ordering me what to think, leftie media elite!”

A related phenomenon occurs in the wake of any big news event which has the potential to bolster existing narratives. If you’ve been on Twitter long enough, you’ll recognise that there is sometimes a feeling of anticipation: people have a reactive take ready to go and are just waiting for someone to express the opinion they are primed to denounce. (Kirsty Allsopp usually obliges in the end.) Some of these takes are driven by a belief that the condemned opinion is widely held, but that your opponents are generally too wily to say it out loud. So when someone does voice it, no matter who they are . . . charge!

It’s hard to capture this feeling in words, but it reminds me of how R Kelly wrote Ignition (Remix) before he’d written a song called Ignition. I definitely felt it at the beginning of the Ukraine invasion, where I could sense in the air that someone was going to express surprise that there was a war in Europe, and would instantly become the Prime Example in a discourse cycle about Eurocentricism in the media.

Now, that’s a valid discourse—in the stupidly honest words of Mark Zuckerberg, “A squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.” The invasion of Ukraine has been getting far more coverage in British and American outlets than, say, the Saudis’ starvation of Yemen, or the bloody conflict in Tigray. And that’s only partly because it’s easy to get to Lviv from a functioning airport, and because Russia is a nuclear-armed power. It’s also about American and European news consumers’ presumed identification with white/Christian/European refugees.

But what was strange was the sense of a readymade reaction to crude, offensive Eurocentric statements forming before any actual inciting incident had happened. And that hair-trigger for confirmation bias, in turn, led to things like the embarrassing incident where 39-year-old Prince William said something completely reasonable—“For our generation, it’s very alien to see this in Europe”—and the first bit got lopped off the pool report, which also added some commentary about how he had compared Ukraine with the Middle East and Africa (he hadn’t). Unfortunately, some commentators were so primed for someone white and high-profile to put their foot in it that their takes went off prematurely at the first sign someone had. Even better—Prince William! The foe of beloved Meghan Markle! He is exactly the kind of guy to say something thoughtless and racist!

Within hours, though, the record had been corrected to include what Prince William actually said, the articles had been updated, and—to their credit—Jake Tapper and Bernice King had deleted their dunk tweets. In fact, the turnabout happened so fast that most of the news reports of the royal visit were about the controversy over the remark (or were updated to be), whereas there is very little straight reporting of the remark itself. It is hard not to see the Prince William incident as an example of a readymade reaction in search of a grievance: a pigeonhole had formed, to misquote Tim Minchin, and by god a pigeon would be found to fill it.

To anyone who wasn’t on Twitter for the hour in which all this went down, the sequence of events must have been bewildering. All those ants, marching in a spiral.

I’ve been trying to think of a term for this phenomenon, where the reaction is disproportionate to the original provocation (or even seems to precede it). I’ve settled on orphan take. An orphan take is an opinion expressed in backlash to a marginal, nebulous or anticipated opposing view. If you see angry tweets or opeds about the horror of a viewpoint you’ve never seen expressed in the wild, that’s an orphan take.

Here’s another recent(ish) example. Every so often I see a tweet about how “the media went insane over Diane Abbott having a mojito on a train but they don’t show any anger over Boris Johnson having parties at Number 10”.

And I’m like, whuuuut? Neither of those things are true.

Dorian Lynskey collected an example here, and here is Pragya Agarwal’s book Sway, in a section on confirmation bias:

The key section reads: “While the media went into a frenzy over an image of Diane Abbott. . . there was considerably less uproar over Michael Gove’s admission that he had taken the class-A drug cocaine.”

These things are hard to quantify, but here’s my assessment. There were a couple of small tabloid stories on Abbott—featuring a photograph of the shadow Home Secretary breaking the law, after all. The only quote even close to calling for her to “face action” was one retired copper in the Sun’s original report. (Again, if you don’t have at least one a retired copper on standby to call for consequences for breaking the law, are you even a tabloid newsdesk, bro?) No Tory big beasts came out to play by offering a condemnatory quote; the only opposition politician quoted by the Sun was a London Assembly member you’ve never heard of. (Sorry, Susan Hall. Again.) Julia Hartley-Brewer offered the opinion that lunchtime train drinking was a sign “something’s going horribly wrong in your life,” but let’s be honest, this will have been only one of about 90 spicy takes JHB will have offered that day, because that’s her job.

What happened next, though, is that the Sun headline went into circulation on Twitter, and lots of lefties defended Abbott—particularly because of the existing narrative that the media picks on her because she’s a black woman. (Personally, I am sympathetic to Diane here, since if I had served in Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet you bet I would have started drinking at lunchtime, but I also think it was a valid story to run since drinking on the Tube is illegal and politicians should obey the laws that they make.)

Anyway, Abbott tweeted an apology, and this was widely covered: Metro, Sky, BBC, Guardian etc. The tone of this wave of coverage was: yeah, this happened, Abbott has apologised, nothing else to see here.

And there wasn’t. There was no caution, no police investigation, and she didn’t lose her shadow cabinet position. M&S did, however, allegedly sell out of mojitos in a can because of the publicity. Briefly. Though if I’m honest, that story smells like bollocks too.

What about Michael Gove’s comparatively easy ride, then? Well, outside the rarefied atmosphere of Twitter, his “cocaine confession” was bigger news than Mojitogate. It came during the Tory leadership race of 2019 and therefore made the front page of the Mail twice. The train mojito did not. Here’s the first:

There was then a lot of commentary about whether it would nuke his leadership chances (I don’t think it helped, certainly) and whether it was “dirty tricks”. However, as with Abbott, the tone of most of the news coverage was about Gove’s apology and regret. He too has not faced police investigation and is now in the Cabinet. But if Abbott “had to apologise”, then so did Gove. And he arguably faced greater political consequences than she did. Also, no one on the right defended him by tweeting in solidarity that they loved a cheeky speedball on the DLR and we should all stop being so judgemental.

Orphan takes are really about narratives. The facts of the case are irrelevant, because “the media go harder on Diane Abbott than Generic Tory Politician X” is the real sentiment being expressed. The details are just garnish.

Since we have a predominantly right-wing press, there is truth to that sentiment, but the use of “the media”—rather than, say, “The Sun”—in this formulation does suggest one good way to spot an orphan take. When the antecedent is either nebulous and disparate (some tweeters) or entirely expected (Tory-supporting paper soft on Tory wrong-doing shock), an orphan take will instead gesture towards a grand coalition to which it is opposed. “People are losing their minds . . .” or “The media are . . .” or “Centrists be like . . .”

Orphan takes are powerful because there is a social cost to challenging them. Again, it’s about narrative. The other narrative that underlies the Abbott story is that racism exists—that it’s harder, on balance, to be a black politician than a white one, and harder to be a female one than a male one, and so as a rare black woman in politics, Abbott faces an intense level of scrutiny. Contesting the narrow facts of Mojitogate is taken to be the same as challenging the narrative underpinning it—disputing the existence of racism itself.

That means there is a huge incentive not to question any particular orphan take, since orphan takes are so often expressing a deeper truth. This is also why many of my favourite journalists have a reputation for being “contrarian” or “heterodox”, by the way. They are the dweebs who think that just because Abbott experiences racism doesn’t mean you can promote whiffy arguments to illustrate that fact.

The hardest challenge for journalism in the social media age is proportion. It’s really, really hard to write about popular sentiment or received wisdom when Twitter in particular is such a distorting force. I’ve done it myself above, in relaying the sense of takes being readied, but not attributing that to anyone. That is merely my perception—and is just as faulty and prone to bias as any other.

One of the most useful words I’ve learned in the last few years is nutpicking: like cherry picking, but with idiots. The Rational Wiki definition linked there quotes the media reporter Kevin Drum: “If the best evidence of wackjobism you can find is a few anonymous nutballs commenting on a blog, then the particular brand of wackjobism you’re complaining about must not be very widespread after all.” So how do writers answer the challenge of conveying proportion—particularly if that means choosing to ignore a story, something which goes against all our instincts?

Yes, there were bad takes about Ukraine being a “civilised” (read: white/western) country, but what proportion of the thousands upon thousands of hours of Ukraine did they comprise? Yes, some people were mean to Diane Abbott over the mojito—but who? And do their opinions carry any weight? Did they lead to any professional or personal consequences for her? Are we really going to spend our time rebutting the bad opinions of Susan Hall, when we still don’t know who she is? (Sorry, Susan Hall.) If someone is “suffering abuse online”, is it harsh disagreement; a torrent of individually-abrasive but collectively harrowing criticism; personal attacks; doxxing; or death threats? Yes, some Nazanin-related hashtags trended, but do 5,000-odd tweets reflect anything at all? Journalists should avoid inflating their opponents beyond their actual size.

This tendency to argue with “people” and amplify “what people are saying” is particularly acute when blame needs to be assigned. I remember a great tweet along the lines of:

My boyfriend clips his toenails in the bath

5 replies 2 retweets 8 likes

White men: 👏 stop 👏 clipping 👏 your 👏 toenails 👏 in 👏 the 👏 bath

787 replies 450 retweets 3,458 likes

There is no better enemy to take on, if you want to make yourself seem righteous but you are also quite lazy, than one which is both vast and nameless. Otherwise it becomes clear that if you draw away the curtain, Wizard of Oz-style, you are having an argument with one guy from Cleethorpes, or a professional shitposter—one of those people who only really exists on Twitter1. The same leftwing tweeters whose entire brands are built on criticising “the media” need to stop replicating one of the media’s most annoying habits: presenting a nutpicked opinion as representative of an entire group.

Until they do, the orphan takes will proliferate, and the pheromone trail will cross again, making everyone angrier, more polarised and more self-righteous2.

There is no way to escape from the ant mill.

Quick Links

Get out the world’s smallest violin.

Lauren Hough’s response to having her LAMBDA book nomination withdrawn is a strong contender in the genre of “witch burnings don’t exist — wait, stop—I’m not a witch!—why are you lighting that kindling?” (Lauren Hough, Substack) The back story in the NYT is here. The incident also reminded me of Aaron Sorkin’s Being The Ricardos, which seems to be about McCarthyism (and therefore, presumably, cancel culture) but ends up delivering the message that the real problem with McCarthyism was that some of its victims weren’t communists.

Why The Left Is Split Over Ukraine (Unherd).

Sophie Gilbert on the new Marilyn Manson documentary, and how his —unfair—vilification over Columbine gave cover to his subsequent misdeeds. (The Atlantic)

Self-promotion zone: I presented Start the Week on Monday, about Welsh identity. Come for me trying to pronounce Y Gododdin, stay for poetry, politics and a surprising confession from one of my guests.

An entire Substack about the conditions which created Labour’s 1997 victory? Sir, you are spoiling us. (Substack) With thanks to Duncan Weldon, who has his own excellent Substack, for the tip.

“Why does Tucker Carlson sound like a Berkeley leftist?” Interesting piece on the US right’s crush on Putin and concomitant hatred for their own liberal democracy. (Antonio Garcia Martinez, Substack)

See you next time!

It’s important to catalogue the exact number of times Britain was a bellend, though.

I showed a draft of this to some other journalists before publication, and one noted: “In the olden days, this sort of stuff would have been done in the Letters pages. And a Times columnist whose piece began ‘I read a letter in the Mirror yesterday...’ would have to jump a pretty bloody high bar to get printed.” He added: “There’s a shortage of good takes, which require thought and effort and actual happenings, and so bad takes tend to drive out good. I also wonder if that’s why we end up gorging on US takes, often about journalists we don’t know at papers we don’t read, because they’re higher quality, even if irrelevant.”

"Orphan take" is a brilliant term. Though I could really use a term for the (I think related) phenomenon of people tweeting "Look at X's latest piece in which they say Evil Thing Y!" when the piece in question explicitly says "I am not saying Evil Thing Y, but rather superficially-similar thing Z..."

This is a legendary post which needs to be read by everyone. Great job!